The call of the crafts – decoys

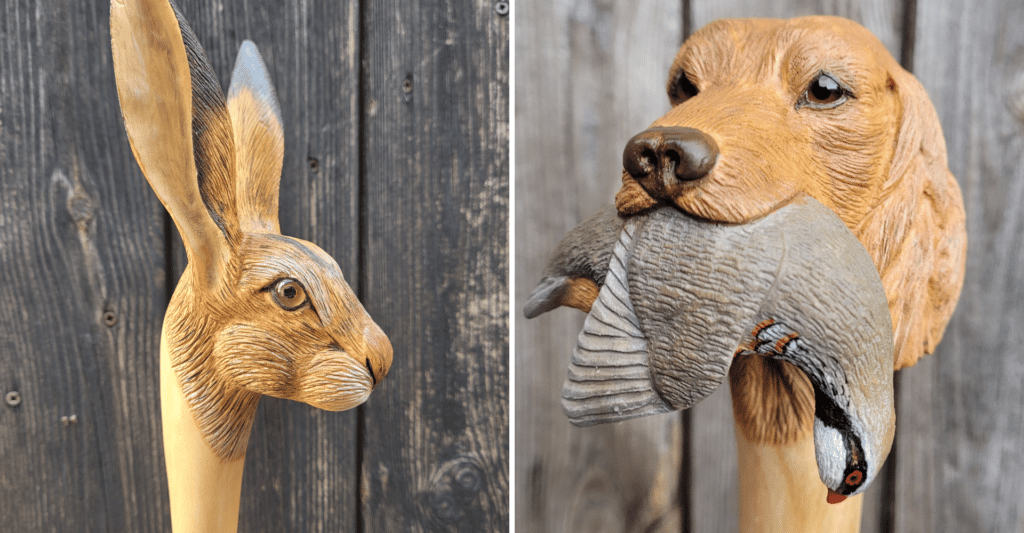

The quality of Trevor’s decoys speaks for itself and his work has been recognised in wood carving championships and a stream of commissions.

Get information on the legal shooting season for mammals and birds in the UK.

Learn about our current conservation projects and how you can get involved.

Comprehensive information and advice from our specialist firearms team.

Everything you need to know about shotgun, rifle and airgun ammunition.

Find our up-to-date information, advice and links to government resources.

Everything you need to know on firearms law and licensing.

All the latest news and advice on general licences and how they affect you.

To appreciate craftsmanship is to look beyond what an item is and delve into how it came to be, says Will Pocklington as he learns more about the journey of three well-known artisans in the shooting community. This article first appeared in the latest issue of Shooting and Conservation magazine.

In a fast-paced world of instant everything, traditional crafts serve as a reassuring nod to the value we still place on hand-made objects. Skills that have been passed down between generations live on. Today’s throwaway culture has an antithesis and it resides in the worn and calloused hands of craftsmen.

To appreciate craftsmanship is to look beyond what an item is and delve into how it came to be. The end product is special because of its journey and the passion and understanding that imbue its creation – qualities that are all but absent in copy-cat items that roll off a production line.

Most of us who shoot have at least one such item. Examples abound in country life and it is all the richer for it. When we invest in these pieces we invest in the people who bring them to fruition. It is the craftsman’s hands, mind and eyes that work in harmony to produce something unique and personal, and it is their story that so often sits at the core of the allure.

In the modern day these people forge a name for themselves and word quickly spreads far and wide. I was eager to learn more about the journey of three popular examples in our community.

There’s something very appealing about using an item you have made yourself for an activity that you love. It’s what had South Yorkshire-based Alan Johnson reaching for the tools in his garage back in 2009 as he followed a step-by-step knifemaking guide in Bushcraft and Survival magazine.

“I’ve been into my shooting for a long time, and a knife is a staple piece of kit,” he explains. “I just fancied the challenge of making my own.”

Alan still has that knife in his cupboard. A rudimental creation, it marked the start of a journey that has seen his interest in the craft evolve from a curiosity to a hobby and now to a profession.

Knives number two and three were made as gifts for friends and family. Then came the enquiries from further afield. Investment in new pieces of equipment – a grinder, a new drill, a bandsaw, a heat treatment oven – followed as orders continued to build. Finally, in 2017, on his fortieth birthday and after a house move which enabled him to build a bigger workshop, Alan took the plunge and set up full-time as Danum Blades, having handed in his notice as a regional training officer for a pest control company.

“It’s a hobby that got out of hand,” he laughs. “I find it very humbling that I can create something using some bits of steel and wood that people really value and appreciate.” But Alan does himself a disservice with such a description; his portfolio is packed with arresting examples of craftsmanship that are now used by shooters and stalkers across the UK.

“People like the idea of buying something from a person they can talk to and relate to, if that makes sense,” answers Alan when I ask him why he thinks so many people opt for a custom-made knife instead of a perfectly capable £10 alternative. “This really became apparent when I started attending shows with my knives,” he continues. “Customers buy into you as a person as much as they do your knives.” It’s a realisation that encouraged Alan to set up his own YouTube channels, for knifemaking and deer stalking.

Most of Alan’s knives are made on a commission basis, but he also offers a selection for sale on his website. Customers can choose from a vast selection of wood, G10 and acrylic – he’s even made handles from mammoth ivory. Options are also aplenty for the pins and the sheaths, and you can even request laser engraving.

“You can really make something that is quite unique, and that’s the other draw of going bespoke – you end up with something much more personalised,” he explains.

Alan hasn’t kept count but guesses he must have made a thousand knives by now. With two treatment stages and the need to finish the knife completely before the sheath can be made to fit perfectly, though, it’s a process that can’t be rushed. These knives are made to last.

Three or four knives leave his workshop in a typical week. Most are for stalkers and shooters and, although social media and an online presence no doubt play their part, Alan remains adamant that many of his knives are still sold through word of mouth.

“It amazes me how often I share mutual friends with someone who lives the opposite side of the country,” he remarks in reference to the close-knit nature of the field sports community.

“Meeting new, like-minded people is a real boon of what I do.”

The extent of demand for custom-made wildfowling calls became clear to Lee Edwards one evening about five years ago. He’d posted a picture of a simple creation on Facebook. “It was nothing fancy, just a greylag call in black acrylic,” he remembers, “but I was absolutely bombarded with enquiries about it.” We’re talking 500 messages in the space of 48 hours.

Lee was vaguely aware of such an appetite, having previously worked on an ad hoc basis for the late Eddie Nixon of Solway Calls. “Eddie was busy enough to need a second pair of hands,” Lee explains. “He gave me a foot in the door. But when he passed away, I stopped for a while.”

It’s been five years since Lee made the very first call to order under his own name. Soon after, he founded Muddy Gutter Calls. He has now produced what he estimates to be between 5,000 and 7,000 of them for customers all over the world, from New Zealand to Canada and Iceland to Pakistan. “I make all of the duck and goose species – several of them can be used for more than one species if you alter the way that you call with them,” he tells me.

From a workshop in his garden – still, remarkably, during his spare time when not working as a full-time joiner – Lee turns six-inch-long blocks of various materials and colours into striking cylinders of beauty and function. They often feature shiny collars and laser engraving.

“You can make a call out of pretty much anything provided it is machinable,” he admits. “Some people use aluminium, different types of wood, antler… I even have a friend who has used whale bones.”

Lee reckons it takes roughly two hours to make a goose call, and a bit longer for duck calls because more filing is involved to achieve the correct pitch and tone.

It is the pitch, tone and ease of use, it seems, that is key to the popularity of Lee’s wares. And that’s testament to his affinity with the birds his customers are keen to mimic. He is an avid ‘fowler and during the season can be found on a marsh somewhere in Scotland with his black lab, Ruby, three or four times a week. His knowledge of the various calls of different species is abundantly clear and something he shares freely in demonstration videos with his followers on social media.

Not surprisingly, his customers are an engaged bunch. Proof takes the shape of feedback he receives from happy buyers. “One guy in Norfolk collects them. He has 48 of my calls now,” Lee mentions.

I ask Lee if he has a favourite call. He pauses briefly. “I sent a mallard call and a whitefront call to a well-known hunting guide in the US a few years back. On his first morning out with them he shot his limit for both species. I heard from him a month later, asking for my address. On my birthday a package arrived and he’d sent the mallard call back to me as a present. ‘I want you to have it’ the note read.”

Hearing back from happy customers with their own stories of special flights and outings isn’t uncommon, according to Lee, but it’s a rewarding and enjoyable part of the job. “I’ve met a lot of people through making the calls,” he says. “And some good friends to boot.”

Mark Davies is a prime example of a hobbyist who fell into a profession almost by accident. He carved his very first stick off the back of a friendly bet. “I saw a stick on a shoot day and jokingly stated that I could do better with a Dremel,” he remembers. “‘Go on then’, my friend told me.” Mark couldn’t resist the challenge.

By his own admission, that first attempt at a grouse turned out like “a golf ball with a bit of a beak”, but it was a starting point and Mark could soon be found making sticks in the little spare time he had as a gamekeeper.

“The carving really appealed to me,” he says. “At first I was just carving any sort of wood I could find. Then I started to buy a few new tools and looked more closely at the wood being used.”

Five years after that first attempt, a few of Mark’s beaters asked if he could make them a stick. “Then word spread, as it does, and before long I had quite a list of people after one,” he explains.

In February 2010, Mark went full-time as ‘Country Sticks’. “By then I had a website and had amassed a library of photos of what I had made. But I’ve never really had to advertise – 95 per cent of my business comes through word of mouth.”

There’s a good chance you’ve seen one of Mark’s sticks on a shoot day. If you have, you’ll be familiar with their level of detail and accuracy. Harder to appreciate is the diversity of Mark’s portfolio.

Name a species and there’s a good chance he’s carved it. Gamebirds aside, he’s ticked off everything from barn owls, kingfishers and ospreys to badgers, pike and herons. Dogs, too. And then there’s the more unusual commissions…

“I really enjoy doing anything out of the ordinary,” Mark tells me. “I have one customer who has dozens of my sticks now. Each time he pays, he writes the details of the next stick he’d like at the bottom of the cheque – and it’s always something different.”

Mark relishes the challenge. He has carved JCB diggers, gargoyles, a Mallard train, even Stephenson’s Rocket! Among his favourites is a stick he made for a friend who has a golden eagle and wanted a carved head on which he could keep the the bird’s hood when not in use.

“Other stickmakers often ask me how I have the patience to take on such projects,” Mark laughs. “What they don’t see is how many stick heads I have thrown on the fire over the years!”

Mark used to start and finish each stick individually, but he learnt that he was burning more heads that way. “Now I tend to have half a dozen on the go at a time,” he says. “I reach a certain stage before putting a stick down and moving on to another. That way, each time I pick them up I’m looking at them with fresh eyes and I can see where I’m going wrong.”

Mostly he uses walnut for the heads – English if he can get it – but also sycamore, spalted beech, ash and chestnut. They all differ in their appearance and characteristics. The softer woods are whittled down with chisels only, whereas a power carver is used for the initial stages on hard species. For the shanks, hazel, blackthorn and ash are go-to choices. “I cut some myself on land where I have permission to do so,” Mark explains. “Often I will buy them in, though, and I have a customer who will swap shanks for finished sticks, which is handy.”

No matter the task, Mark is always trying to better his last stick. After thousands of unique specimens that are treasured the world over, who knows what will leave his workshop next?

The quality of Trevor’s decoys speaks for itself and his work has been recognised in wood carving championships and a stream of commissions.

Classique Feathers’ range has grown to include a vast array of country home decor.

Sign up to our weekly newsletter and get all the latest updates straight to your inbox.

© 2023 British Association for Shooting and Conservation. Registered Office: Marford Mill, Rossett, Wrexham, LL12 0HL – Registered Society No: 28488R. BASC is a trading name of the British Association for Shooting and Conservation Limited which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) under firm reference number 311937.

If you have any questions or complaints about your BASC membership insurance cover, please email us. More information about resolving complaints can be found on the FCA website or on the EU ODR platform.

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

This website uses Google Analytics to collect anonymous information such as the number of visitors to the site, and the most popular pages.

Keeping this cookie enabled helps us to improve our website.

Please enable Strictly Necessary Cookies first so that we can save your preferences!

More information about our Cookie Policy